|

IBM managed this rapid time-to-market through the utilization of lower-capacity platters. While the flagship Cheetah 10K.6, Fujitsu’s MAP3146, and the upcoming Maxtor Atlas 10k IV all utilize four 36-gigabyte disks, the 146Z10 uses 6 platters that store just under than 25 GB each. IBM specs the drives average read seek times at 4.7 milliseconds. An 8-megabyte buffer and 5 year warranty round out the package.

There’s been much speculation running rampant on the merger of IBM and Hitachi’s hard disk divisions into a new separate entity. According to our contacts at IBM, however, the 146Z10 remains a pure Big Blue product. The new company is not expected to merge technologies or product plans until the transition is complete.

The 146Z10 is one of the first Ultra320 SCSI drives to hit our testbed. Ultra320’s most highly-touted feature, of course, is an increase in the throughput ceiling to 320 MB/sec. Keep in mind that the current transfer rate champion, the Cheetah 15K.3, pushes 76 MB/sec in its outer sectors. While figures like these threaten Ultra2 SCSI’s 80 MB/sec barrier, Ultra160’s 160 MB/sec limit maintains plenty of headroom. It is only in multi-drive scenarios that 160 MB/sec bottlenecks can arise. Our base drive tests occur with a single unit as the only active device on the host adapter. In such a setup, any performance advantages that Ultra320 (along with the requisite higher-bandwidth 64-bit PCI slots) would deliver over 160 are negligible. For our performance tests, we’re going to take advantage of the specification’s backwards compatibility and run the drive in Ultra160 mode off of our current host adapter. Bear in mind that improved bandwidth is only one of the benefits that Ultra320 delivers. A host of improvements in protocol and error correction should elevate data integrity and device interoperability to new levels.

Low-Level ResultsFor diagnostic purposes only, StorageReview measures the following low-level parameters: Average Read Access Time– An average of 25,000 random accesses of a single sector each conducted through IPEAK SPT’s AnalyzeDisk suite. The high sample size permits a much more accurate reading than most typical benchmarks deliver and provides an excellent figure with which one may contrast the claimed access time (claimed seek time + the drive spindle speed’s average rotational latency) provided by manufacturers. WB99 Disk/Read Transfer Rate – Begin– The sequential transfer rate attained by the outermost zones in the hard disk. The figure typically represents the highest sustained transfer rate a drive delivers. WB99 Disk/Read Transfer Rate – End– The sequential transfer rate attained by the innermost zones in the hard disk. The figure typically represents the lowest sustained transfer rate a drive delivers. |

For more information, please click here.

|

Note: Scores on top are better. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IC35L146UWDY10 Average Read Service Time |

IC35L146UWDY10 Average Write Service Time

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Ultrastar 146Z10 turns in an average read access time of 8.4 milliseconds, a figure a bit on the high side when contrasted with the competition. Subtracting 3 milliseconds to account for the average rotational latency of a 10,000 RPM spindle speed yields an average measured read seek time of 5.4 ms… well off Big Blue’s 4.7 ms claim.

An average write access time of 8.7 milliseconds is closer to that of competing drives. Only Seagate’s Cheetah 10K.6 manages to differentiate itself here.

|

Note: Scores on top are better. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

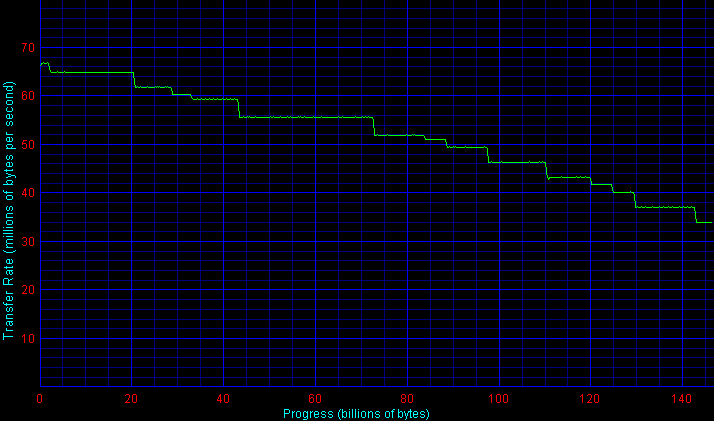

IC35L146UWDY10 Transfer Rate

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Though it features a lower areal density than some competitors (25 GB/platter vs 36/GB platter), the Ultrastar nonetheless turns in a respectable outer-zone transfer rate of 65.1 MB/sec. As the test moves inwards, however, the drive exhibits significant decay with inner-zone rates weighing in at just 36.2 MB/sec.

Single-User PerformanceStorageReview uses the following tests to assess non-server use: StorageReview.com Office DriveMark 2002– A capture of 30 minutes of actual computer productivity use that exactingly recreates a typical office-style multitasking environment. The applications include: Outlook XP, Word XP, Excel XP, PowerPoint XP, Calypso (a freeware e-mail client), SecureCRT v3.3 (a telnet/SSH client), CuteFTP Pro v1.0 (an FTP/SSH client), ICQ 2000b), Palm Hotsync 4.0, Gravity 2.3 (a Usenet/newsgroups client), PaintShop Pro v7.0, Media Player v8 for the occasional MP3, and Internet Explorer 6.0. StorageReview.com High-End DriveMark 2002– A capture of VeriTest’s Content Creation Winstone 2001 suite. Applications include Adobe Photoshop v5.5, Adobe Premiere v5.1, Macromedia Director v8.0, Macromedia Dreamweaver v3.0, Netscape Navigator v4.73, and Sonic Foundry Sound Forge v4.5. Unlike typical productivity applications, high-end audio- and video- editing programs are run in a more serial and less multitasked manner. The High-End DriveMark includes significantly more sequential transfers and write (as opposed to read) operations. |

StorageReview.com Bootup DriveMark 2002– A capture of the rather unusual Windows XP bootup process. Windows XP’s boot procedure involves significantly different access patterns and queue depths than those found in other disk accesses. This test recreates Windows XP’s bootup from the initial bootstrap load all the way to initialization and loading of the following memory-resident utilities: Dimension4 (a time synchronizer), Norton Antivirus 2002 AutoProtect, Palm Hotsync v4.0, and ICQ 2000b.

StorageReview.com Gaming DriveMark 2002– A weighted average of the disk accesses featured in five popular PC games: Lionhead’s Black & White v1.1, Valve’s Half-Life: Counterstrike v1.3, Blizzard’s Diablo 2: Lord of Destruction v1.09b, Maxis’s The Sims: House Party v1.0, and Epic’s Unreal Tournament v4.36. Games, of course, are not multitasked- all five titles were run in a serial fashion featuring approximately half an hour of play time per game.

For more information, please click here.

|

Note: Scores on top are better. |

StorageReview.com’s Office DriveMark 2002 pegs the Ultrastar 146Z10 at 433 IOs/sec. Though within striking distance of Seagate’s Cheetah 10K.6, the 146Z10 can’t keep up with Fujitsu’s category-leading MAP3146.

This scenario plays itself out across all other Desktop DriveMark suites. The SR Bootup DriveMark 2002, a test that features unusually high queue depths, is of particular note. Fujitsu’s MAP excels while the Ultrastar stumbles, yielding an enormous margin of 44%.

Multi-User PerformanceStorageReview uses the following tests to assess server performance: StorageReview.com File Server DriveMark 2002– A mix of synthetically-created reads and writes through IOMeter that attempts to model the heavily random access that a dedicated file server experiences. Individual tests are run under loads with 1 I/O, 4 I/Os, 16 I/Os, and 64 I/Os outstanding. The Server DriveMark is a convenient at-a-glance figure derived from the weighted average of results obtained from the four different loads. StorageReview.com Web Server DriveMark 2002– A mix of synthetically-created reads through IOMeter that attempts to model the heavily random access that a dedicated web server experiences. Individual tests are run under loads with 1 I/O, 4 I/Os, 16 I/Os, and 64 I/Os outstanding. The Server DriveMark is a convenient at-a-glance figure derived from the weighted average of results obtained from the four different loads. For more information click here. |

|

Note: Scores on top are better. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IBM’s drive, while competitive with the Atlas 10k III, can’t quite keep up with next-generation drives from Seagate and Fujitsu in multi-user scenarios.

Legacy PerformanceeTesting Lab’s WinBench 99 Disk WinMark tests are benchmarks that attempt to measure desktop performance through a rather dated recording of high-level applications. Despite their age, the Disk WinMarks are somewhat of an industry standard. The following results serve only as a reference; SR does not factor them into final judgments and recommends that readers do the same. |

|

Note: Scores on top are better. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Heat and NoiseIdle Noise– The sound pressure emitted from a drive measured at a distance of 18 millimeters. The close-field measurement allows for increased resolution between drive sound pressures and eliminates interactions from outside environmental noise. Note that while the measurement is an A-weighted decibel score that weighs frequencies in proportion to human ear sensitivity, a low score does not necessarily predict whether or not a drive will exhibit a high-pitch whine that some may find intrusive. Conversely, a high score does not necessarily indicate that the drive exhibits an intrusive noise envelope. Net Drive Temperature– The highest temperature recorded from a 16-point sample of a drive’s top plate after it has been under heavy load for 80 minutes. The figures provided are net temperatures representing the difference between the measured drive temperature and ambient temperature. For more information, please click here. |

|

Note: Scores on top are better. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There was a time when IBM SCSI drives were renown for their quiet operation. The Ultrastar 9ES’s combination of decent speed and quiet/cool operation comes to mind.

Technical limitations unfortunately precluded SR from objective sound pressure level measurements of the Ultrastar 146Z10. As described in our methodology article, we use an AT power supply with its fan disabled to achieve as quiet an ambient environment as possible. The 146Z10, however, can’t be powered up without a live host adapter connection which requires introduction of additional equipment that adversely affects the ambient background.

Subjectively speaking, however, the drive’s idle noise is significantly higher than that exhibited by the Cheetah 10K.6 or the MAP3735. Though there’s a noticeable high-pitched squeal, the majority of noise comes in a midrange “hum.” The 146Z10 also exhibits a recalibration routine similar to that of the Ultrastar 73LZX. Every minute or so, when idle, the drive screeches and chirps away for about a second, much more intrusive than the drive’s normal seek noise.

At 31.6 degrees Celsius above ambient, the 146Z10’s operating temperature weighs in substantially higher than competing offerings. One should consider active cooling when integrating the drive into a system not housed in a dedicated server room.

ReliabilityThe StorageReview.com Reliability Survey aims to amalgamate individual reader experiences with various hard disks into a comprehensive warehouse of information from which meaningful results may be extracted. A multiple-layer filter sifts through collected data, silently omitting questionable results or results from questionable participants. A proprietary analysis engine then processes the qualified dataset. SR presents results to readers through a percentile ranking system. According to filtered and analyzed data collected from participating StorageReview.com readers, the |

According to filtered and analyzed data collected from participating StorageReview.com readers, a predecessor of the

IBM Ultrastar 146Z10, the

IBM Ultrastar 73LZX

, is more reliable than of the other drives in the survey that meet a certain minimum floor of participation.

Note that the percentages in bold above may change as more information continues to be collected and analyzed. For more information, to input your experience with these and/or other drives, and to view comprehensive results, please visit the SR Drive Reliability Survey.

ConclusionWe’re disappointed to report that we can’t recommend the Ultrastar 146Z10. Fujitsu’s MAP3146 offers better performance, lower heat and noise levels, and a lower platter count. Excepting brand loyalty, there’s no reason to choose the Ultrastar over Seagate’s Cheetah 10K.6 and especially over the Fujitsu. |

Amazon

Amazon