WD’s next-generation Raptor is here! The VelociRaptor WD3000BLFS doubles the line’s capacity to 300 gigabytes and reduces the line’s form factor to a modern 2.5″ profile. How much higher does the latest entry in this storied family raise the performance bar? Join StorageReview as we take a look at the newest drive out of Lake Forest.

Update 4/6/10 – Western Digital VelociRaptor 600GB Review

|

Though WD rapidly followed up its initial 37 GB release with a significantly improved 74 GB model, almost two years separated the Raptor WD740GD and its successor, the Raptor WD1500ADFD. As the family’s first native SATA design, the latter Raptor again stood as WD’s performance-oriented offering for nearly sixteen months. In that time, terabyte behemoths hit the channel and have chipped away at and in some cases even surpassed the venerable third-generation Raptor in sheer performance. Its 150-gigabyte capacity also seemed more and more constricting as the months ticked by.

The majority of today’s desktop machines still expect standard 3.5″ drives. While some users seeking the ultimate in acoustic and thermal performance have taken to mounting notebook-oriented 2.5″ designs into their home rigs, the consumer world remains a 3.5″ landscape. Many readers have found out that desktop cases, 2.5″ drives, and rails that convert such units to 3.5″ form factors don’t always get along. Screw holes frequently fail to line up and necessitate custom solutions such as drilling to get everything aligned.

WD has addressed the issue by outfitting initial shipments of the VelociRaptor in a custom 2.5″ to 3.5″ converter. Dubbed IcePAK, this aluminum chassis permits the drive to be mounted in any standard 3.5″ bay. Though it’s somewhat stylishly cut with heatsink-like fins, IcePAK’s purpose is primarily form factor conversion, not heat distribution. It should be noted that an IcePAK-mounted VelociRaptor does not perfectly mimic a true 3.5″ drive when it comes to rear-connection alignment; IcePAK drives won’t work with the standard SATA/SAS backplanes found in many rack-mounted servers. Standard SATA cables, of course, work just fine. For enterprise use, the firm plans to ship VelociRaptors sans the 3.5″ chassis.

The VelociRaptor’s 2.5″ design, as one would expect, incorporates two reduced-diameter platters packing 150 gigabytes each. The narrowed span leads to a manufacturer-claimed seek time of just 4.2 milliseconds, a 12% improvement over that of the WD1500ADFD.

Though a roomy 32-megabyte buffer accompanies some of today’s terabyte drives, WD has chosen to stick with a more conservative 16 MB cache. In contrast to the 1.5 Gb/sec-equipped WD1500ADFD, the VelociRaptor represents the first iteration of the family to ship with a 3 Gb/sec SATA interface. Reflecting the series’ continued enterprise-orientation, the WD3000BFLS ships with a claimed MTBF of 1.4 million hours and a 5-year warranty.

In the tests that follow, we’ll pit an engineering sample of WD’s VelociRaptor WD3000BFLS against the following drives:

| Hitachi Deskstar 7K1000 (1000 GB) | Competing large-capacity 7200 RPM Drive |

| Seagate Barracuda ES.2 (1000 GB) | Competing large-capacity 7200 RPM Drive |

| Seagate Cheetah NS (400 GB) | Industry-standard 10,000 RPM SAS Drive |

| Western Digital Caviar GP (1000 GB) | Manufacturer’s large-capacity 7200 RPM Drive |

| Western Digital Caviar WD7500AAKS (750 GB) | Manufacturer’s performance-oriented 7200 RPM Drive |

| Western Digital Raptor WD1500ADFD (150 GB) | Predecessor to the review unit |

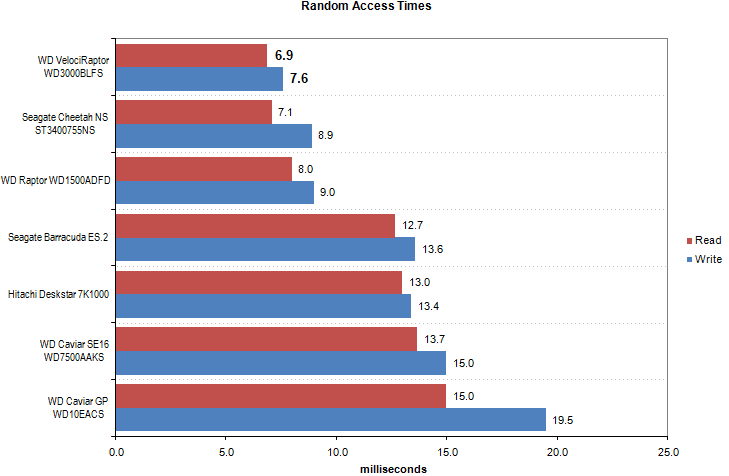

Access Time and Transfer RateFor diagnostic purposes only, StorageReview measures the following low-level parameters: Average Read Access Time– An average of 25,000 random read accesses of a single sector each conducted through IPEAK SPT’s AnalyzeDisk suite. The high sample size permits a much more accurate reading than most typical benchmarks deliver and provides an excellent figure with which one may contrast the claimed access time (claimed seek time + the drive spindle speed’s average rotational latency) provided by manufacturers. Average Write Access Time– An average of 25,000 random write accesses of a single sector each conducted through IPEAK SPT’s AnalyzeDisk suite. The high sample size permits a much more accurate reading than most typical benchmarks deliver. Due to differences in read and write head technology, seeks involving writes generally take more time than read accesses. |

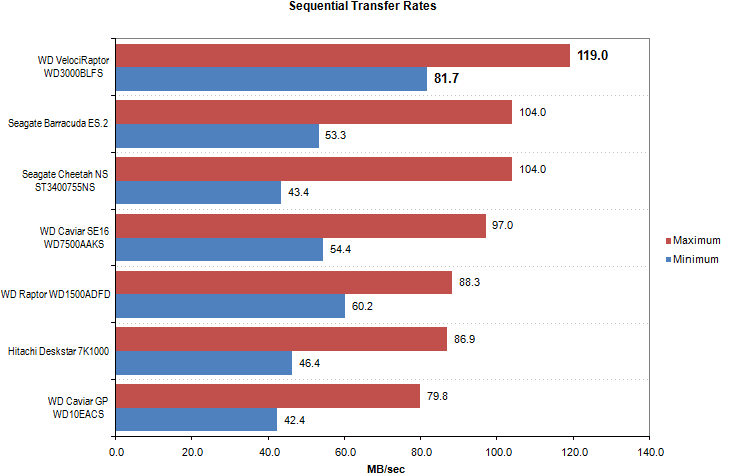

WB99 Disk/Read Transfer Rate – Begin– The sequential transfer rate attained by the outermost zones in the hard disk. The figure typically represents the highest sustained transfer rate a drive delivers.

WB99 Disk/Read Transfer Rate – End– The sequential transfer rate attained by the innermost zones in the hard disk. The figure typically represents the lowest sustained transfer rate a drive delivers.

For more information, please click here.

| Some Perspective

It is important to remember that access time and transfer rate measurements are mostly diagnostic in nature and not really measurements of “performance” per se. Assessing these two specs is quite similar to running a processor “benchmark” that confirms “yes, this processor really runs at 2.4 GHz and really does feature a 400 MHz FSB.” Many additional factors combine to yield aggregate high-level hard disk performance above and beyond these two easily measured yet largely irrelevant metrics. In the end, drives, like all other PC components, should be evaluated via application-level performance. Over the next few pages, this is exactly what we will do. Read on! |

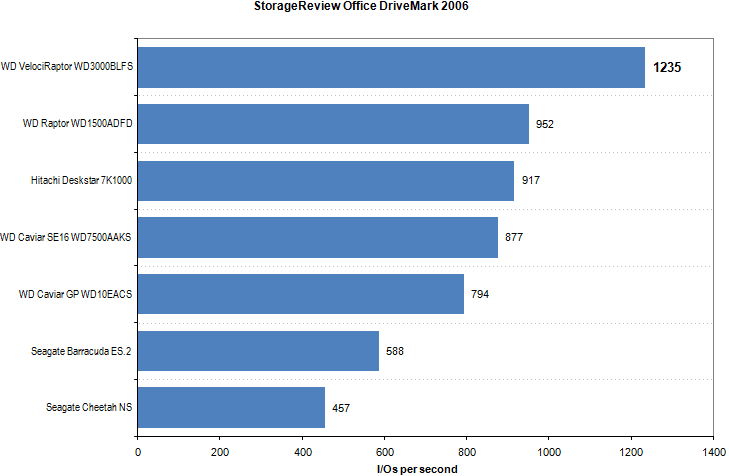

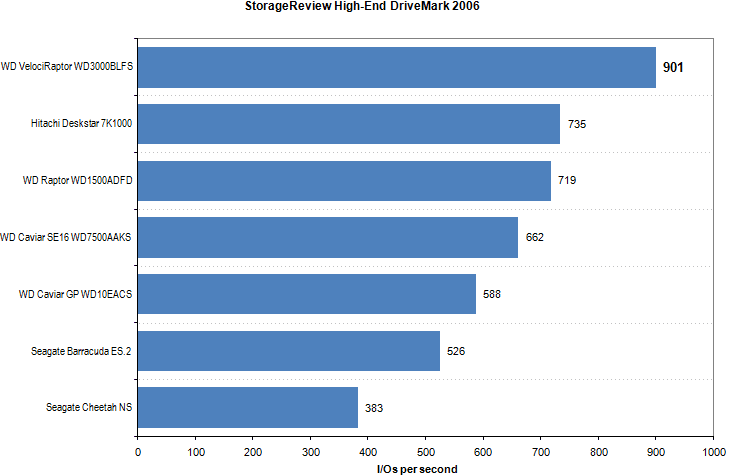

Single-User PerformanceStorageReview uses the following tests to assess non-server use: StorageReview.com Office DriveMark 2006– A capture of VeriTest’s Business Winstone 2004 suite. Applications include Microsoft’s Office XP (Word, Excel, Access, Outlook, and Project), Internet Explorer 6.0, Symantec Antivirus 2002 and Winzip 9.0 executed in a lightly-multitasked manner. StorageReview.com High-End DriveMark 2006– A capture of VeriTest’s Multimedia Content Creation Winstone 2004 suite. Applications include Adobe Photoshop v7.01, Adobe Premiere v6.5, Macromedia Director MX v9.0, Macromedia Dreamweaver MX v6.1, Microsoft Windows Media Encoder 9.0, Newtek Lightwave 3D 7.5b, and Steinberg Wavelab 4.0f run in a lightly-multitasked manner. For more information, please click here. |

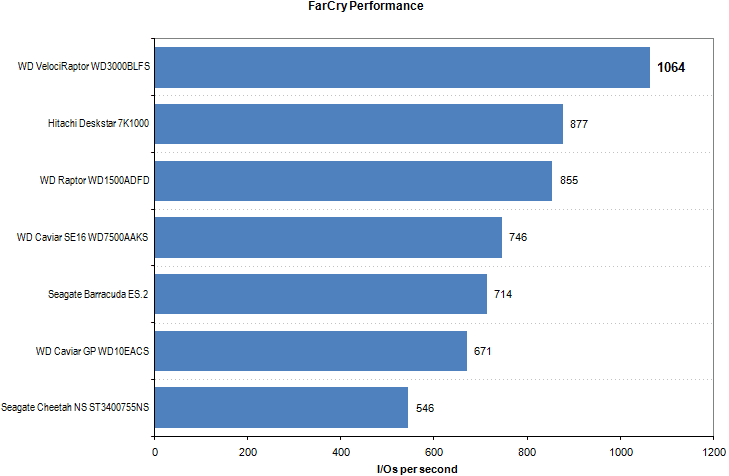

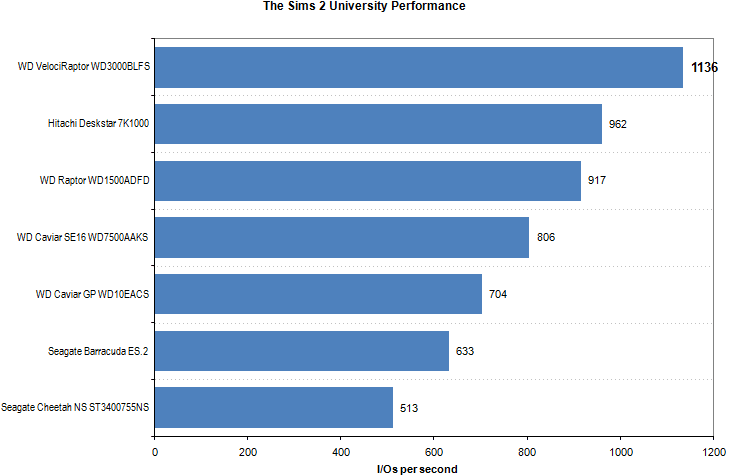

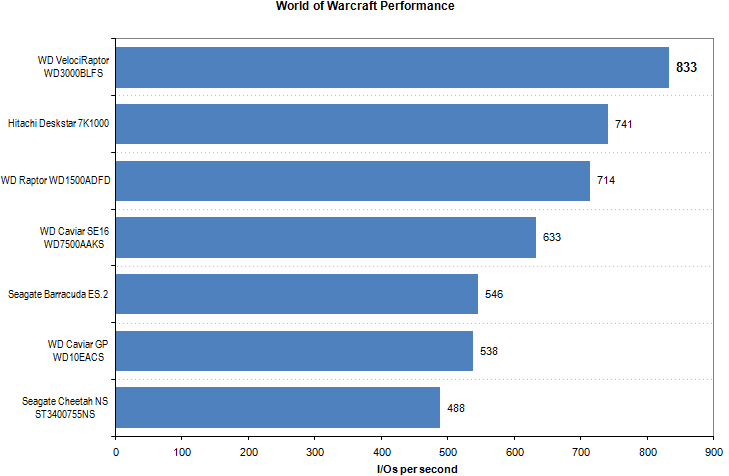

Gaming PerformanceThree decidedly different entertainment titles cover gaming performance in StorageReview’s test suite. FarCry, a first-person shooter, remains infamous for its lengthy map loads when switching levels. The Sims 2, though often referred to as a “people simulator,” is in its heart a strategy game and spends considerable time accessing the disk when loading houses and lots. Finally, World of Warcraft represents the testbed’s role-playing entry; it issues disk accesses when switching continents/dungeons as well as when loading new textures into RAM on the fly. For more information, please click here. |

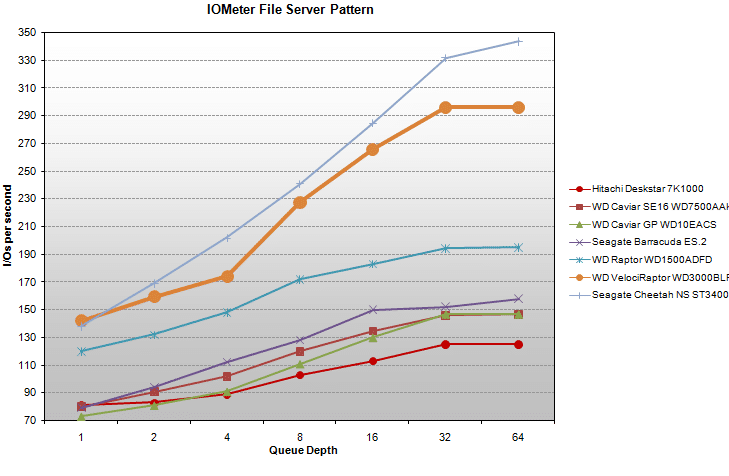

Multi-User PerformanceUnlike single-user machines (whether a desktop or workstation), servers undergo highly random, non-localized access. StorageReview simulates these multi-user loads using IOMeter. The IOMeter File Server pattern balances a majority of reads and minority of writes spanning requests of varying sizes. IOMeter also facilitates user-configurable load levels by maintaining queue levels (outstanding I/Os) of a specified depth. Our tests start with the File Server pattern with a depth of 1 and double continuously until depth reaches 128 outstanding I/Os. Drives with any sort of command queuing abilities will always be tested with such features enabled. Unlike single-user patterns, multi-user loads always benefit when requests are reordered for more efficient retrieval. For more information click here. |

Veteran SR readers may recall that the original 37 GB Raptor WD360GD failed to include any kind of command queuing at all. Its successor, the 74 GB WD740GD incorporated legacy ATA-4 command queuing that provided some erratic scaling under load. WD’s first native SATA Raptor design, the WD1500ADFD, scaled more smoothly but also more modestly than the WD740GD.

As evidenced by the graph above, the VelociRaptor turns in significantly higher IOps under all levels of load than its predecessor and remains within shooting distance of Seagate’s Cheetah NS. The NS remains a particularly apt comparison as it is not only the largest 10K RPM drive around but, as a 2.5″ design “hard mounted” in a 3.5″ chassis, also in a way shares the WD3000BLFS’s design philosophy.

WD’s design manages to maintain a respectable showing vis-a-vis the Cheetah under most queue depths but stumbles slightly at a concurrency of 4 I/Os. Even so, the VelociRaptor’s improvements are quite encouraging and give WD its strongest case yet in selling SATA to the entry- to mid-level server market.

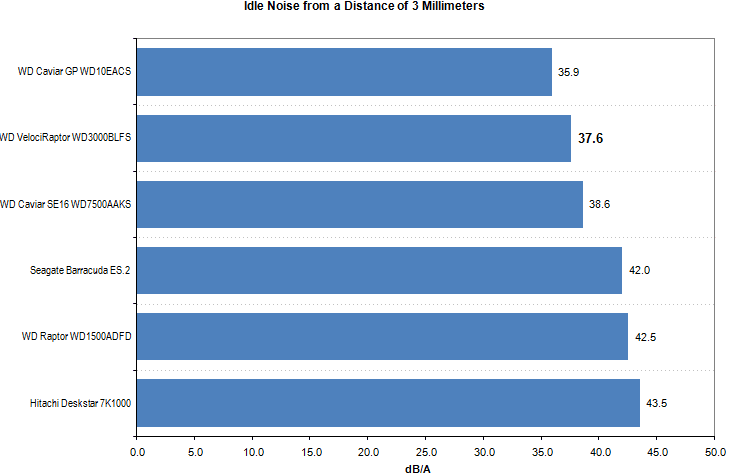

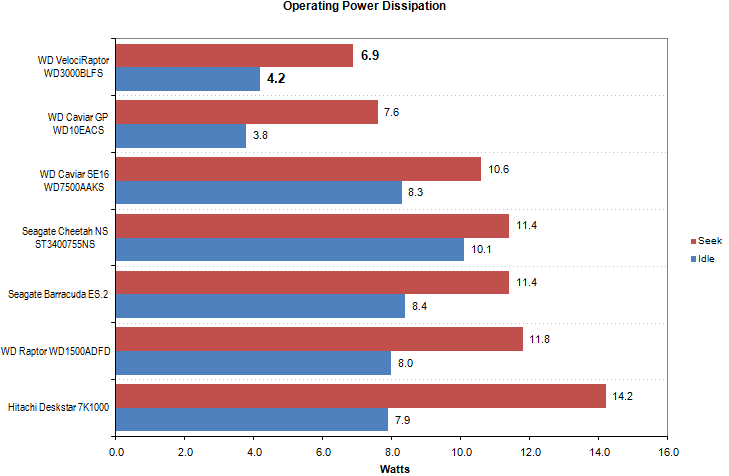

Noise and Power MeasurementsIdle Noise– The sound pressure emitted from a drive measured at a distance of 3 millimeters. The close-field measurement allows for increased resolution between drive sound pressures and eliminates interactions from outside environmental noise. Note that while the measurement is an A-weighted decibel score that weighs frequencies in proportion to human ear sensitivity, a low score does not necessarily predict whether or not a drive will exhibit a high-pitch whine that some may find intrusive. Conversely, a high score does not necessarily indicate that the drive exhibits an intrusive noise profile. Operating Power Dissipation– The power consumed by a drive, measured both while idle and when performing fully random seeks. In the relatively closed environment of a computer case, power dissipation correlates highly with drive temperature. The greater a drive’s power draw, the more significant its effect on the chassis’ internal temperature. |

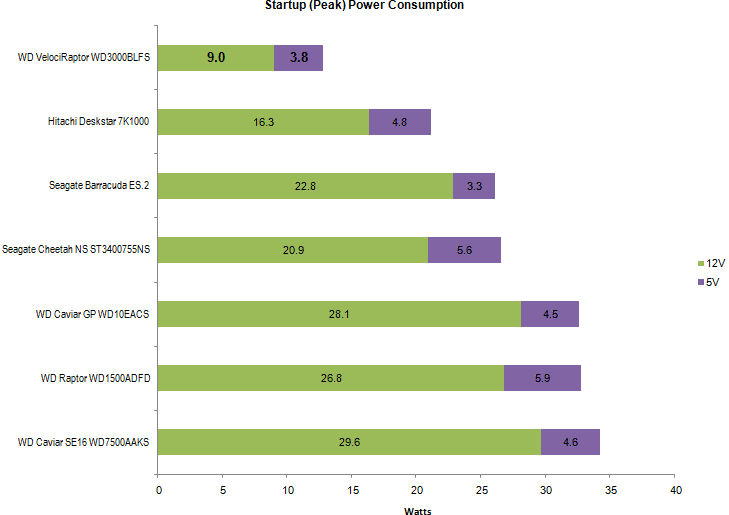

Startup (Peak) Power Dissipation– The maximum power dissipated by a drive upon initial spin-up. This figure is relevant when a system features a large number of drives. Though most controllers feature logic that can stagger the spin-up of individual drives, peak power dissipation may nonetheless be of concern in very large arrays or in cases where a staggered start is not feasible. Generally speaking, drives hit peak power draw at different times on the 5V and 12V rails. The 12V peak usually occurs in the midst of initial spin-up. The 5V rail, however, usually hits maximum upon actuator initialization.

For more information, please click here.

ReliabilityThe StorageReview.com Reliability Survey aims to amalgamate individual reader experiences with various hard disks into a comprehensive warehouse of information from which meaningful results may be extracted. A multiple-layer filter sifts through collected data, silently omitting questionable results or results from questionable participants. A proprietary analysis engine then processes the qualified dataset. SR presents results to readers through a percentile ranking system. According to filtered and analyzed data collected from participating StorageReview.com readers, the Western Digital VelociRaptor WD3000BLFS is more reliable than of the other drives in the survey that meet a certain minimum floor of participation. |

According to filtered and analyzed data collected from participating StorageReview.com readers, a predecessor of the Western Digital Raptor WD3000BLFS, the Western Digital Raptor WD1500ADFD , is more reliable than of the other drives in the survey that meet a certain minimum floor of participation.

Note that the percentages in bold above may change as more information continues to be collected and analyzed. For more information, to input your experience with these and/or other drives, and to view comprehensive results, please visit the SR Drive Reliability Survey.

ConclusionWestern Digital continues to stand alone as the only manufacturer offering a 10,000 RPM spindle speed coupled with a standard SATA interface. Here at StorageReview we have admittedly been quite enthusiastic with each new Raptor release. The improvements between the VelociRaptor and its predecessor, however, dwarf all previous upgrades. The drive’s single-user scores, climbing by as much as 30% when compared to the WD1500ADFD’s, blow away those of every other disc. Its noise and power measurements are among the lowest we have ever recorded. Topping it all off, the unit’s multi-user scores for the first time bring a Raptor drive within striking distance of that of a 10K RPM SAS unit. Oh, let’s not forget about the doubled capacity… 300 GB finally brings WD’s 10K offering back into an eminently-usable range in today’s capacity-hungry world. |

Perhaps most encouraging is the manufacturer’s claim that the engineering sample evaluated here is about “90% optimized.” While cynics may point out that the final version may slip when contrasted to the awesome results presented above, WD confidently states that the performance we’re seeing remains on the conservative side. While initial VelociRaptor shipments will go exclusively to a certain gaming-oriented OEM, WD estimates that individual units will hit distribution in mid-May. In addition to updating readers with figures drawn from a retail sample, we’ll take a look how the VelociRaptor (obviously magnetic media’s best overall single-user performance entry) holds up against some solid state offerings. Stay tuned!

Update 4/6/10 – Western Digital VelociRaptor 600GB Review